The Colonel Alexander Lillington Chapter was chartered on 21 January 2018; D. Henry Campbell was the organizing president.

John Alexander Lillington, planter, politician, and soldier, was the son of John and Sarah Porter Lillington and the grandson of Alexander Lillington who arrived in the Albemarle Sound area in the early Proprietary years, participated in Culpepper’s Rebellion, and subsequently remained active in precinct and provincial government until his death in 1697. His father was one of four children of Alexander by the latter’s second marriage. Born in Beaufort Precinct, John Alexander Lillington, the revolutionary, was orphaned and raised in the Cape Fear by Edward Moseley, his uncle and legal guardian.

Named John Alexander, but generally using only the middle name, Lillington was moderately active in local and provincial affairs. As a lieutenant in the New Topsail Company of militia, he held to repel the Spanish invasion of Brunswick in 1748. He represented New Hanover County in the colonial Assembly in 1762, and in the county her served as a justice of the peace from 1764 to 1767 and from 1774 to 1775. The assembly appointed him commissioner to lay off a town at Sand Hill in 1754, and a commissioner to survey the Duplin-New Hanover County boundary in 1766.

Best known for his military exploits in the Revolution, Lillington first evidenced publicly his incipient Whiggism in the Stamp Act crisis when he, John Ashe, and Thomas Lloyd, representing the inhabitants of the Cape Fear, indicated to Governor William Tryon their hope that the restrictions on commerce in the Cape Fear River would be lifted. Like many eastern politicos, Lillington subsequently supported the governor in the Regulator campaigns, serving as a lieutenant colonel and then colonel commandant of a company of light infantry on the 1768 expedition to Hillsborough. In 1771 he was assistant quartermaster general in the campaign that ended with the defeat of the Regulators in the Battle of Alamance.

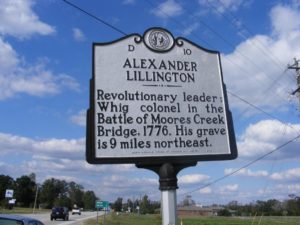

As the Revolution approached, Lillington was elected to the New Hanover County Committee of Safety in 1775 and as one of the county’s delegates to the Third Provincial Congress, which met at Hillsborough in August 1775. Appointed by the congress colonel of a battalion of minutemen in the Wilmington District, he played a conspicuous, albeit debatable, role in the Patriot victory at Moore’s Creek Bridge on February 27, 1776. Lillington arrived first at the battlefield but was soon reinforced by Richard Caswell who took command of the forces. Together they thwarted the advance of the Loyalists in a victory for which the ultimate credit probably belonged to General James Moore. Concerning the field of battle, however, the partisans of Lillington and Caswell wrangle over the merits of their respective heroes in a running debate that probably emanated from the observations of Joseph Seawell Jones, A Defence of the Revolutionary History of North Carolina (1934).

On April 15, 1776 the Fourth Provincial Congress appointed Lillington colonel of the Sixth Regiment of North Carolina Continentals. He resigned on December 31, 1776, ostensibly pleading advanced age but perhaps trying to avoid desperate supply conditions or attempting to open an avenue for political advancement. In 1777 he represented New Hanover County in the Assembly, and on February 4, 1779 he was named brigadier general of the militia in the Wilmington District. As the British moved south to threaten Charles Town in 1780, North Carolina militiamen commanded by Lillington were sent to aid General Benjamin Lincoln. Since the term of enlistment for the mission expired before the fall of Charles Town, Lillington and at least half of his force returned to North Caroline; the remainder of the North Carolina militia surrendered with Lincoln on May 12, 1780.

From the capture of Wilmington in January 1781 to the departure of the British later in the year, Lillington remained busy fending against the forays of Major James H. Craig and the many Loyalists who appeared to support the king. Supply deficiencies and ammunition shortages caused Lillington to become increasingly distressed with the progress of the war. He castigated the Continental supply officers who heavy-handedly sequestered supplies and excoriated the rest of the state for failing to come to the aid of Wilmington and its environs.

At the end of the war Lillington reclaimed most of his estate that had been under British control. Lillington Hall, his impressive home, had been saved from the British torch (according to tradition, by Loyalists who retained great admiration and respect for Lillington), but many of his slaves had been lost, of which he had twenty-two according to a 1763 tax list, had been lost. Fortunately, his valuable library was preserved. At an unknown date the State Library of North Carolina acquired a portion of Lillington’s books and in the 1950s the North Carolina Collection at Chapel Hill obtained those volumes as an “associated collection”.

Lillington, reputedly a large man of exceptional strength, married Sarah Watters, daughter of Brunswick County planter William Watters. They had four children: John (d. 1785). George (1765-94), Sarah, and Mary. John served as a lieutenant in North Carolina’s First Continental Regiment, justice of the peace in New Hanover County, and a trustee of Innes Academy. General John Alexander Lillington was buried according to Anglican rites in the family cemetery near Lillington Hall, now marked “Lillington Cemetery” and located in Pender County.

Source: Dictionary of North Carolina Biography edited by William S. Powell; Vol. 4; pg. 66